Content note: some of the wording below is ablist and racist language. It has been copied unedited.

Listen along to a reading of the following poem by its author, Eli Clare:

Strangers offer me Christian prayers or crystals and vitamins, always with the same intent—to touch me, fix me, mend my cerebral palsy, if only I will comply. They cry over me, wrap their arms around my shoulders, kiss my cheek. After five decades of these kinds of interactions, I still don’t know how to rebuff their pity, how to tell them the simple truth that I’m not broken. Even if there were a cure for brain cells that died at birth, I’d refuse. I have no idea who I’d be without my tremoring and tense muscles, slurring tongue. They assume me unnatural, want to make me normal, take for granted the need and desire for cure.

Strangers ask me, “What’s your defect?” To them, my body-mind just doesn’t work right, defect being a variation of broken, supposedly neutral. But think of the things called defective—the

mp3 player that won’t turn on, the car that never ran reliably. They end up in the bottom drawer, dumpster, scrap yard. Defects are disposable and abnormal, body-minds or objects to eradicate.Strangers pat me on the head. They whisper platitudes in my ear, clichés about courage and inspiration. They enthuse about how remarkable I am. They declare me special. Not long ago, a white woman, wearing dream-catcher earrings and a fringed leather tunic with a medicine wheel painted on its back, grabbed me in a bear hug. She told me that I, like all people who tremor, was a natural shaman. Yes, a shaman! In that split second, racism and ableism tumbled into each other yet again, the entitlement that leads white people to co-opt indigenous spiritualities tangling into the ableist stereotypes that bestow disabled people with spiritual qualities. She whispered in my ear that if I were trained, I could become a great healer, directing me never to forget my specialness. Oh, how special disabled people are: We have special education, special needs, special spiritual abilities. That word drips condescension. It’s no better than being defective.

Strangers, neighbors, and bullies have long called me retard. It doesn’t happen so often now. Still, there’s a guy down the road, who, when he’s drunk, taunts me as I walk by with my dog. But when I was a child, retard was a daily occurrence. Once on a camping trip with my family, I joined a whole crowd of kids playing tag in and around the picnic shelter. A slow, clumsy nine-year-old, I quickly became “it.” I chased and chased but caught no one. The game turned. Kids came close, ducked away, yelling retard. Frustrated, I yelled back for awhile. Retard became monkey. My playmates circled me. Their words became a torrent. You’re a monkey. Monkey. Monkey. I gulped. I choked. I sobbed. Frustration, shame, humiliation swallowed me. My body-mind crumpled. It lasted two minutes or two hours—I don’t know. When my father appeared, the circle scattered. Even as the word monkey connected me to the non-human natural world, I became supremely unnatural.

All these kids, adults, strangers join a legacy of naming disabled people not quite human. They approach me with prayers and vitamins, taunts and endless questions, convinced that I’m broken, special, an inspiration, a tragedy, in need of cure, disposable, the momentum of centuries behind them. They have left me with sorrow, shame, and self-loathing.

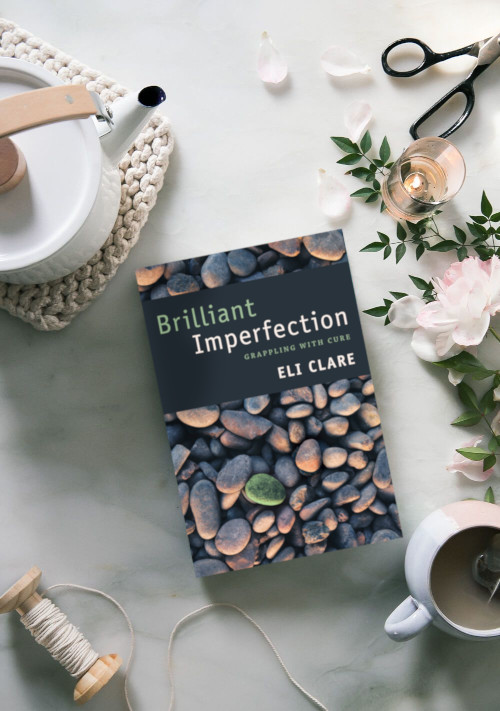

I wanted to share this poem, which is an excerpt from the award winning book ‘Brilliant Imperfection‘, to shine a light on the perspective it brings. I listened to the author recite it aloud on a podcast, the audio is provided above. Episode 6, on which author Eli Clare is featured, addresses some of the ethical questions that should be considered when seeking a cure for disability. Does the person affected by the condition want a cure? Does curing a disability change who they are? And to what extent are able bodied loved ones entitled to make that decision for them?

The podcast in question is called ‘Unlocking Bryson’s Brain‘, the subject of which is a little boy who suffers from a rare genetic condition that leaves him unable to communicate or make decisions for himself. I found it very moving to listen to the careful considerations, the tireless pursuit for a cure and the unconditional love from Bryson’s parents and brother.

The poem’s reading was quite touching to me, not only due to its brutal eloquence and the impact of hearing a perspective on this subject from a person directly affected by disability, but also because to some extent I relate to it. As my MS progresses, so does my disability, which in turn inevitably affects how I not only perceive myself but perhaps more importantly how the world perceives me. This is underscored by the Dutch word for disability, which is literally translated to ‘invalid’. Not valid. Does not count. Disregarded. Disposable?

I peed myself once, in the middle of the park, as I was walking my dog. The acute loss of bladder control made it empty itself completely, my black sweats soaking through, urine running into my shoes as it cooled on its way down my legs. It was the single most dehuminising experience I’ve had to date and as I forced myself to keep my head high and my gait steady, I rushed home where I burst into tears as I peeled off the soaked garments before hiding from the world under a warm comforting stream of water.

Dehumanising, less than human, my personhood momentarily taken away by the lack of control over a basic bodily function, and replaced by my shame. And yet I consider myself lucky for being able to (mostly) control my mind. I’m able to speak, put feelings into thoughts, thoughts into words, words into sentences and muse on the complexities of ethical questions. This poem made me reflect on what life is like for people that aren’t able to do all that, and what life may look like when (if?) I reach that point.

I continue to muse, until I can’t.